skip to main |

skip to sidebar

On Thursday I was invited to participate in an extremely inspiring tour of school garden work in Sacramento and Davis. The tour was hosted by Dan Desmond, a major guru in the field of garden-based education. Dan is a Fellow in the Kellogg Foundation's Food & Society Policy Fellowship, and he has connected his fellow fellows to garden-based education as a key link in the chain of food systems, nutrition education and policy.

On Thursday I was invited to participate in an extremely inspiring tour of school garden work in Sacramento and Davis. The tour was hosted by Dan Desmond, a major guru in the field of garden-based education. Dan is a Fellow in the Kellogg Foundation's Food & Society Policy Fellowship, and he has connected his fellow fellows to garden-based education as a key link in the chain of food systems, nutrition education and policy.

I enjoyed an exciting day of getting to know these fellows. They are amazing role models for those of us working to build careers in the world of food systems, sustainable agriculture, nutrition and youth education.

Dan Desmond, UC Cooperative Extension

Melinda Hemmelgarn, 'Food Sleuth', Media Literacy specialist

Dr. Jennifer Wilkins, Cornell University & Cornell Farm to School Program

Susan Roberts, Director, Food & Society Policy Fellowship

Fern Gale Estrow, Nutrition Consultant (friend of the Fellows, not a Fellow herself)

Not only were my tour-mates inspiring, but the sites we visited were truly life-changing! In spite of the super intense central valley heat (110 degrees at least!!) we saw some beautiful urban farms run for youth, and even by youth, to bring healthy and sustainable food systems and education to youth and their communities. Our itinerary:

California Foundation for Agriculture in the Classroom

Judy Culbertson, Executive Director

Connected to the state Farm Bureau and the national ag in the classroom org, CFAITC provides glossy curriculum materials to help teachers educate young people about agriculture. Although limited by the requirement of no negative press for agriculture--period--their materials are great.

Grant High School–Garden of Ethnic American Treasures (EAT)

Ann Marie Kennedy, Garden Teacher and Director

High school students run this beautiful school garden as an after school intership for school credit (ag vocational credit, too, a new one for us city kids) and in school as part of biology classes. They grow, harvest, cook and eat their own food, run a cut flower business, and run a salsa buisness that they manage and market for. This summer Workreation students, part of a Sacramento city youth employment program, visit the garden once a week to work, cook and eat fresh food. This program is all about youth leadership and youth development. They have a LOT to teach the rest of us!

Soil Born Farm

Soil Born Farm

Shawn Harrison, Executive Director

This is a full on urban farm, right next to Jonas Salk Middle School in Sacramento. Besides providing garden-based education at the school they are a real working farm, with farm apprentices, that sells produce through their CSA and other markets, while also providing food to the local low-income community and education to the students at the school. A real farm, with profit-making activities! Amazing. Pics on this post were taken at Soil Born Farm (see school bus in background!).

University of California, Davis: Sustainable Food Systems

Mark Van Horn, Director, Organic Farming, Student Farm & Ecological Gardens

Children's Garden: Carol Hillhouse, Director; Jeri Ohmart & Katie Hume, Coordinators

Jane Pinckney, Growing Connections

UC Davis has a beautiful student farm and children's garden that has a CSA for students and faculty, educational garden tours for kids and school groups, training and support for teachers and schools in school garden-based education, and an internship program for university students. So much stuff going on! They are getting ready to start a new center of sustainable ag studies including an undergraduate major.

UC School Nutrition Research Group

Another connected group is the UC Davis Department of Nutrition, presented to us by another food systems role model, Marilyn Briggs. Marilyn was the assistant superintendent for the state of California and state Director of Nutrition Services, and she is now working on her doctorate in nutrition sciences at Davis with researchers like Sheri Zidenberg-Cherr. This group is creating the Center for Nutrition Education in Schools and has big plans to support California schools and families through nutrition education including garden-based education.

The folks and UC Davis and at CFAITC are both founding members of the California School Garden Network, another of my favorite resources.

The folks and UC Davis and at CFAITC are both founding members of the California School Garden Network, another of my favorite resources.

school garden

food system

Food & Society Policy Fellowship

nutrition education

sustainable agriculture

school nutrition

research

Since the earliest reflections on the nonprofit or voluntary sector in the US, people have described the nonprofit sector as a pillar of US democracy. Without nonprofits, we would not have the kind of freedom we enjoy today. It is that simple.

In fact, school garden-based education programs in schools can play a key role in solving the major challenges facing US public education: they can impact youth health, low academic achievement and chaotic school climate, and even the drastic inequality between urban public schools and predominantly white suburban schools.

Pretty bold statements, right? Theory and research are on my side! Let me explain.

Theory: Nonprofits as Mediating Institutions

Theory: Nonprofits as Mediating Institutions

Many theorists, starting with Alexis de Tocqueville in 1840, have remarked that voluntary associations in civil life are directly linked to equality in US society. Why? Our founding fathers intentionally created a decentralized system, so no individual would ever have too much power. The result? We came up with another way for individuals to have power and voice: nonprofits. Nonprofits mediate between the public and private spheres, bringing private values into the public sector (Berger & Neuhaus, 1977). Without these, the political system would be detached from our values and daily realities. Active participation of the people is necessary to bring meaning and values into those large, faceless government bureacracies, and to bring the voice of communities into the political system. How many times have you felt helpless, powerless, and treated as less than human when you, alone, deal with tax offices, parking tickets, the justice system, or even the school system?!

How do people in the US band together to voice their needs and make changes? The voluntary sector. All the major social movements have worked through nonprofits, from abolition through civil rights to now.

According to this theory, we would expect public education to be a huge, dehumanizing government bureacracy, neglecting the voices and values of the people, as long as it is not connected to the voluntary sector. What do you think?

Public Education: Factory, Bureaucracy or Community?

In fact, studies show exactly that!

- Civil society and democracy have deteriorated in the US public education system in the last 100 years as local control is stripped away, schools are consolidated into large districts run by distant officials, and state and federal regulation is greatly expanded (Finn et al., 2000). Community responsibility is way down.

- As a result, inequality and segregation are growing at a horrific rate, in successful schools in suburban, white and middle-class areas and failing urban schools serving low-income families of color. Teachers in dilapidated and overcrowded urban schools are under demands from above to use classroom methods developed for factories or for prison inmates, reducing schools to centers of "direct command and absolute control." Teachers struggle to maintain human relationships under such conditions, (Kozol, 2005).

- In urban school districts, efficient, professionalized, and standardized schools have cultivated a culture of power, in which teachers learn “deficit” views of parents, and see low-income parents of color with disdain and disrespect, and at fault for the barriers to their children’s success, while concentrated poverty and racism are the real causes (Warren, 2005).

Under these conditions of extreme structural inequality, it is no surprise that we find very little voluntary activity, few PTA groups, and very low parent involvement in urban public schools.

There is Hope! Parent Organizing in Schools

If you take a closer look at your neighborhood schools, you will undoubtedly find inspiring examples of community members rising up to organize voluntary activity and inject community values into these seemingly impenetrable and bureaucratic schools.

Warren (2005) and Gold et al. (2004) offer examples of community groups like Oakland Community Organizations and Chicago's Logan Square Neighborhood Association that have successfully improved failing urban schools. Such organizations empower parents through group programs that address the inequality of racism and poverty while giving parents new skills and opportunities to contribute meaningfully to their children’s schools. The key is building social capital, or leveraging strong personal relationships to enable groups of people to make change. When groups come together, in voluntary action (i.e. nonprofits or mediating instutitions), those individual parents can hold governments accountable for the sickening injustice in public schools.

Putting the Pieces Together: School Gardens!

Now let me tell you the reasons why school gardens can help schools do all this and more.

1. School garden programs can build social capital and leadership in order to transform parent involvement in public education.

- All four of my case study schools described parent involvement as a crucial piece of the school garden program. At one school, parents created and sustained the garden. At the other three, the school garden has begun to create and sustain parent involvement. These are urban schools where the above issues are serious, and parents come to the garden anxious to voice opinions on a wide range of issues.

- Schools report that gardens provide an entrance to school involvement for many parents, particularly immigrant parents with agrarian backgrounds (CDE, 2002), who may feel uncomfortable in other aspects of the school, but bring great knowledge and experience to the garden.

- A successful program in San Bernardino used school gardens to build meaningful school participation among Latina mothers. The mothers created gardening skill workshops, gardening space at their children’s school, an adult aerobics class, and got the ear of the school principal, with the goal of improving youth and adult health and nutrition (Silberstein & Vega, 2004).

2. School Garden-based Education builds youths' attitudes, relationships and skills necessary for participation in civil life, also creating "civil society" in the internal school community.

- Urban Sprouts own preliminary research results show that school garden programs are powerful ways to build youth and adult relationships, and youth resiliency assets like responsibility, self-efficacy, cooperation and communication (Ratcliffe et al, 2006).

- Youth development theory shows that these assets prepare students for success as participating citizens in early adulthood (Gambone et al., 1997).

- Having a garden may have school-wide effects on school climate and culture, as relationships and values of care developed in the school garden translate to the school community as a whole (Racliffe et al., 2006; Comnes, 1999).

- School garden programs often lead to other school-wide improvement projects, educational campaigns, and other youth-led leadership projects.

So, we see that school gardens can build participation and equality within public schools. In the four case studies, the school gardens are supported by voluntary (nonprofit) organizations.

The Big Question: is it necessary that school gardens be supported by community nonprofits, in order to build civil society and equality in public schools? If government in the form of school districts were to take over or partner in the administration of school garden programs, would their role as mediating institutions be changed or diminished?

Stay tuned, and next time I'll discuss partnership between nonprofits and government.

(see comments for Works Cited)

school garden

nonprofit organization

nonprofit theory

civil society

Tocqueville

Continuing from last post about the compatibility between school garden programs and the nonprofit sector, this time I'll cover some of the potential weaknesses of the nonprofit sector, which suggest that partnering with the government sector (like the public school system) might benefit us.

Continuing from last post about the compatibility between school garden programs and the nonprofit sector, this time I'll cover some of the potential weaknesses of the nonprofit sector, which suggest that partnering with the government sector (like the public school system) might benefit us.

Theory: In his theory of Voluntary Failure, Lester Salamon (1995) identifies four potential weaknesses of the nonprofit (NP) sector.

Philanthropic insufficiency—NPs tend not to generate enough reliable funding to meet the demand for services. This is due in part to the “free rider” problem: giving relies on voluntary donations, so individuals have the incentive to let others bear most of the cost of providing a given service. Also, giving is affected by the ups and downs of the economy as well as by geographic availability of philanthropic and wealthy individuals, both of which tend to provide less funding when and where it is needed most.

Philanthropic particularism— philanthropic individuals tend to favor certain subgroups, such as those they themselves belong to, more than others. Those individuals who either provide resources or organize nonprofit organizations may not adequately represent those communities most in need of resources, often leaving substantial gaps in coverage of service.

Philanthropic paternalism—the most influential and powerful members of a community may control its charitable resources and may determine the goals and activities of the sector in an undemocratic way. Those most in need of charitable services will not be able to make decisions regarding the services available to them, causing a dependent relationship between those giving and receiving charitable aid.

Philanthropic amateurism— NPs often provide amateur services staffed by volunteers, lacking professional training and professionalized models of service provision. Fortunately, trends in the last century have favored professionalized care in many subsectors of the nonprofit sector, but school garden-based education still has a ways to go!

Moving on to the Case Studies!

I looked at stats on all the public school garden programs in San Francisco along with my case study interviews, keeping voluntary failure theory in mind, and noticed the following possible trends:

- More SF elementary schools have gardens than middle and high schools. (85% of SF school gardens serve elementary schools; 40% of all elemenary schools have gardens, compared to 18% of middle schools and 10% of high schools);

- More school gardens serve San Francisco’s western neighborhoods than the city’s south and eastern neighborhoods, where low-income families are concentrated (36% of gardens are in the south and/or east);

- Schools identified by SFUSD as low-performing are underrepresented in schools with gardens, particularly among middle schools;

- Parent involvement: more likely for schools with strong PTAs to have school gardens. Are better-resourced schools more likely to have strong PTAs?

- Community nonprofits: more likely to target under-served communities. Is there a link between community socioeconomic status and the effectiveness of PTAs compared to community nonprofits as a support structure for school gardens?

- Need to professionalize field of garden-based education: need secure, full-time positions in order to retain high-quality trained school garden educators and leaders, unlikely to be accomplished by amateur voluntary associations like PTAs or Garden Committees made up of parents and teachers only.

Any thoughts or feedback so far? Next post I'll describe another way of looking at the nonprofit sector, as a central core pillar of our US democracy, the generator of civil society, participation and voice. Stay tuned!

school garden

nonprofit organization

nonprofit theory

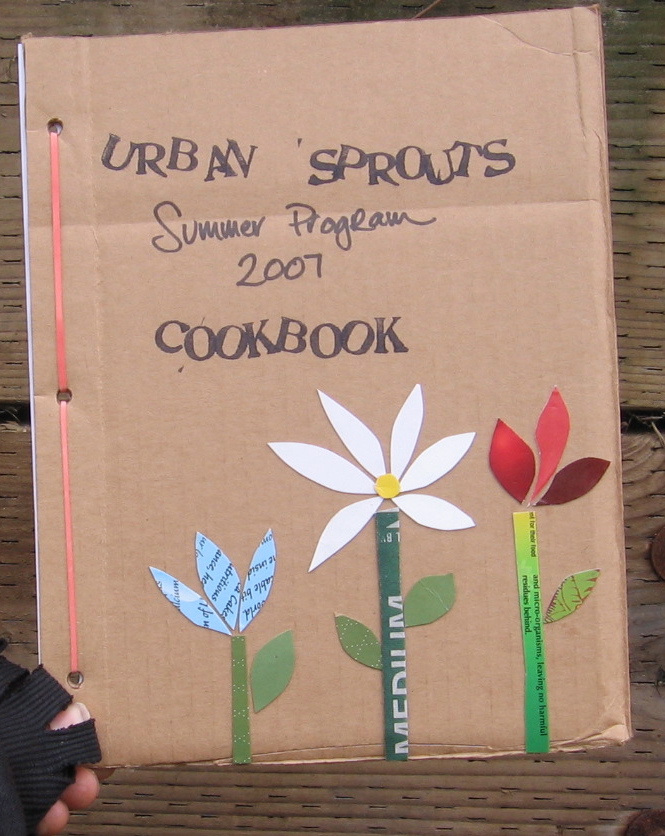

Summer is here, schools are empty, and Urban Sprouts is in rest and reflection mode. Instead of teaching classes, I am focusing on my own classes as a student, in USF's Masters of Nonprofit Administration program. USF provides a strong theoretical background for all those nonprofit skills most of us learn as we go.

Summer is here, schools are empty, and Urban Sprouts is in rest and reflection mode. Instead of teaching classes, I am focusing on my own classes as a student, in USF's Masters of Nonprofit Administration program. USF provides a strong theoretical background for all those nonprofit skills most of us learn as we go.

Our first course covered the history of nonprofits in the US and theories of how and why the nonprofit sector operates. I wrote a paper on the school garden movement in the Bay Area. I wanted to know if it makes sense that we use the nonprofit sector to provide important educational services inside the public school district. Are we just giving the government cool stuff for free? I learned some interesting things through my research, which resulted in Urban Sprouts' decisions 1) to deepen our government partnerships, and 2) to develop a program to intentionally involve middle and high school parents in our school garden work.

In the next few posts, I'll tell you more about what I learned.

First, I found that the nonprofit or voluntary sector is often used to provide school gardens because the public or government sector doesn't.

Theory: The first theories I looked at, market failure and government failure* theories, explain that the free market will not provide the right amount of a public good, because people are not willing pay for something that they can get for free. That's why governments use tax dollars to pay for things like bridges, libraries and national defense. However, governments can only provide things that the majority of people know they want. Services that are innovative, new, untested, will go unprovided. This may leave a significant number of people unsatisfied. Here the nonprofit sector comes in. It meets the need for diverse, experimental and grassroots activities, initiated by us, the people, without waiting around for the big, slow government system to kick in and meet our needs.

Case Studies: I gathered information on four school gardens to use as case studies, three in SF and one in the South Bay. I found that:- All four gardens were supported by voluntary organizations (aka nonprofits)

- Three were initiated by parents and/or teachers and one by an outside nonprofit based in the neighborhood

- Schools say they need School Garden Coordinators: teachers cannot drive school garden programs alone, due to time constraints and lack of knowledge.

- All four schools chose not to administer the school garden program through the schools (local district bureaucracy), because of: School budget constraints; Delays in processing donations and receiving funds; Loss of flexibility by running funding and staffing decisions through district ;Administrative instability: changes in district leadership, school administration; Political instability: changes in district-wide goals and priorities.

- All four chose voluntary sector solutions to administer the school garden program: one PTA, two school garden nonprofit orgs, one other community nonprofit.

Next time: weaknesses of the nonprofit sector!

P.S. I know you're used to cute stories about what the kids are doing, so tell me if you think this stuff is boring!

* Good reading: Salamon, Lester M. (1995). Partners in Public Service; Smith, Steven Rathgeb, and Lipsky, Michael. (1993). Nonprofits for Hire: The Welfare State in the Age of Contracting.

school garden

nonprofit organization

nonprofit theory

On Thursday I was invited to participate in an extremely inspiring tour of school garden work in Sacramento and Davis. The tour was hosted by Dan Desmond, a major guru in the field of garden-based education. Dan is a Fellow in the Kellogg Foundation's Food & Society Policy Fellowship, and he has connected his fellow fellows to garden-based education as a key link in the chain of food systems, nutrition education and policy.

On Thursday I was invited to participate in an extremely inspiring tour of school garden work in Sacramento and Davis. The tour was hosted by Dan Desmond, a major guru in the field of garden-based education. Dan is a Fellow in the Kellogg Foundation's Food & Society Policy Fellowship, and he has connected his fellow fellows to garden-based education as a key link in the chain of food systems, nutrition education and policy. Soil Born Farm

Soil Born Farm The folks and UC Davis and at CFAITC are both founding members of the California School Garden Network, another of my favorite resources.

The folks and UC Davis and at CFAITC are both founding members of the California School Garden Network, another of my favorite resources.